The Vienna-Stadlau project is a residential complex that was built as rental housing within the framework of social housing (subsidized with public funds). A housing project to which exactly the same framework conditions (and financial restrictions) applied as to all other subsidized housing projects in Vienna.

The project was awarded in 1988 as a result of an “expert procedure” in which ecological construction, solar energy use and timber construction were sought.

The competition project comprised 19 residential units, with ARGE Architekten Reinberg-Treberspurg-Raith being commissioned with 10 residential units and the community building, while 9 further apartments were awarded to a second team of participants within the urban development concept. The architects were commissioned not only with the architectural work, but also – as general planners – with the structural engineering and building physics, which was certainly not insignificant for the overall result.

The basic ideas and concepts were

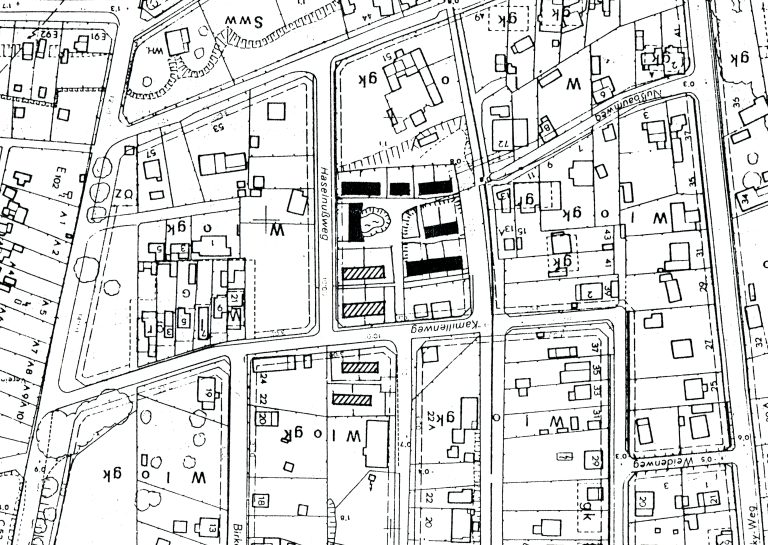

Urban planning

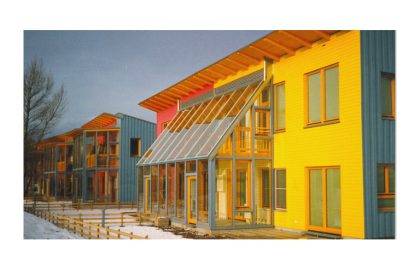

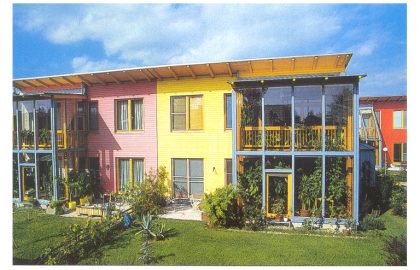

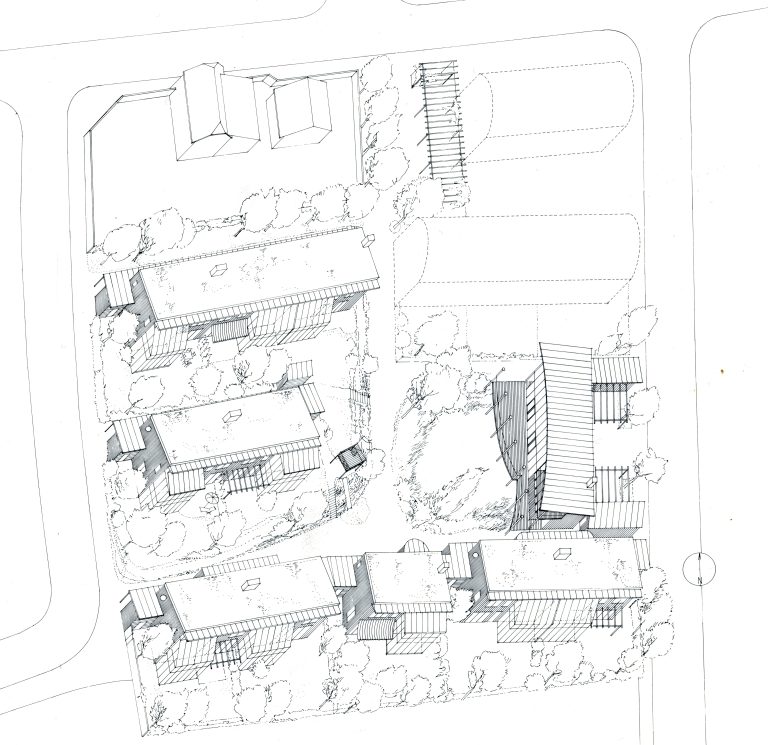

The existing buildings, mostly self-built suburban “urban sprawl”, were considered to be quite sympathetic in character (“suburban poetry”): the new estate was also to retain a somewhat provisional simplicity and the existing small scale and “permeability” were to be preserved.

At the same time, the project should be the impetus for a reassessment of the settlement result (without appearing as a foreign body). The attractiveness of living close to nature with generous open spaces, the proximity to the water (former Danube floodplains) and the simple construction were to be preserved with simple technologies and materials on a new qualitative level.

Thus, deliberately no “urban spaces” (streets, squares) were offered, but rather a varied and intensively usable juxtaposition of different private, semi-public and public nature-related areas.

An existing pond – which had sunk during the course of the Danube regulation – was restored and became the common center of the complex.

This pond is also home to the community house, which is completely open to the rest of the complex and, together with a terrace and the lake, forms the overarching communal area.

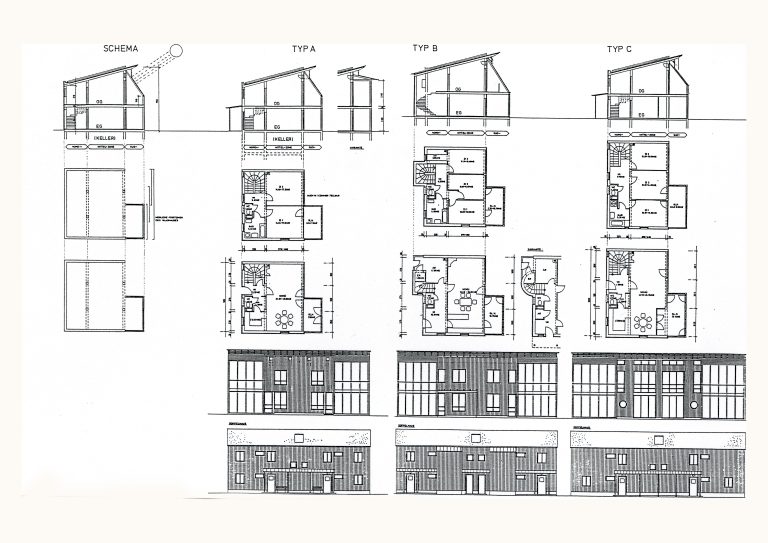

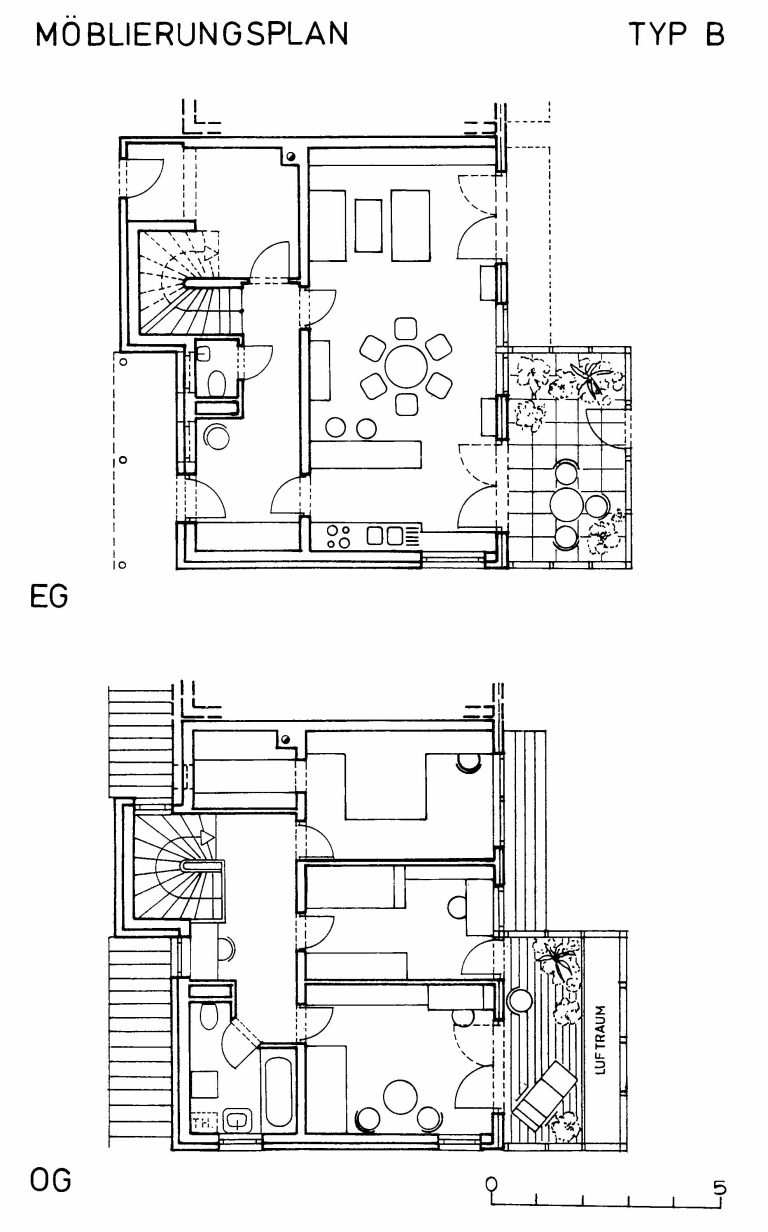

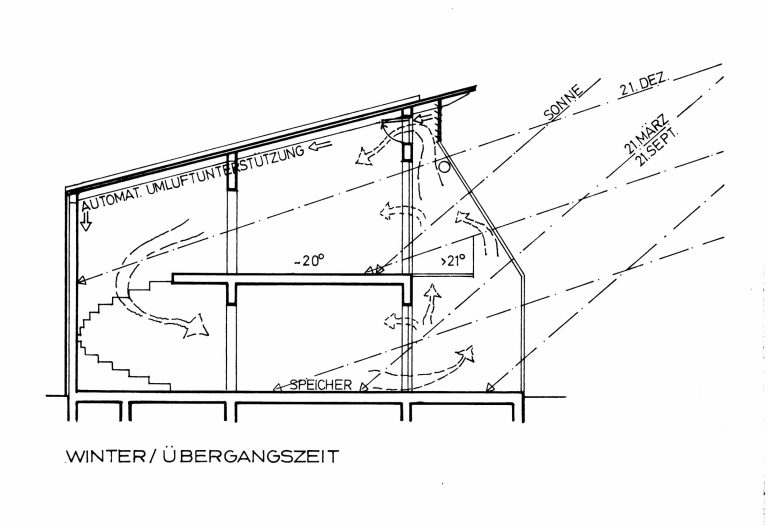

Types of houses

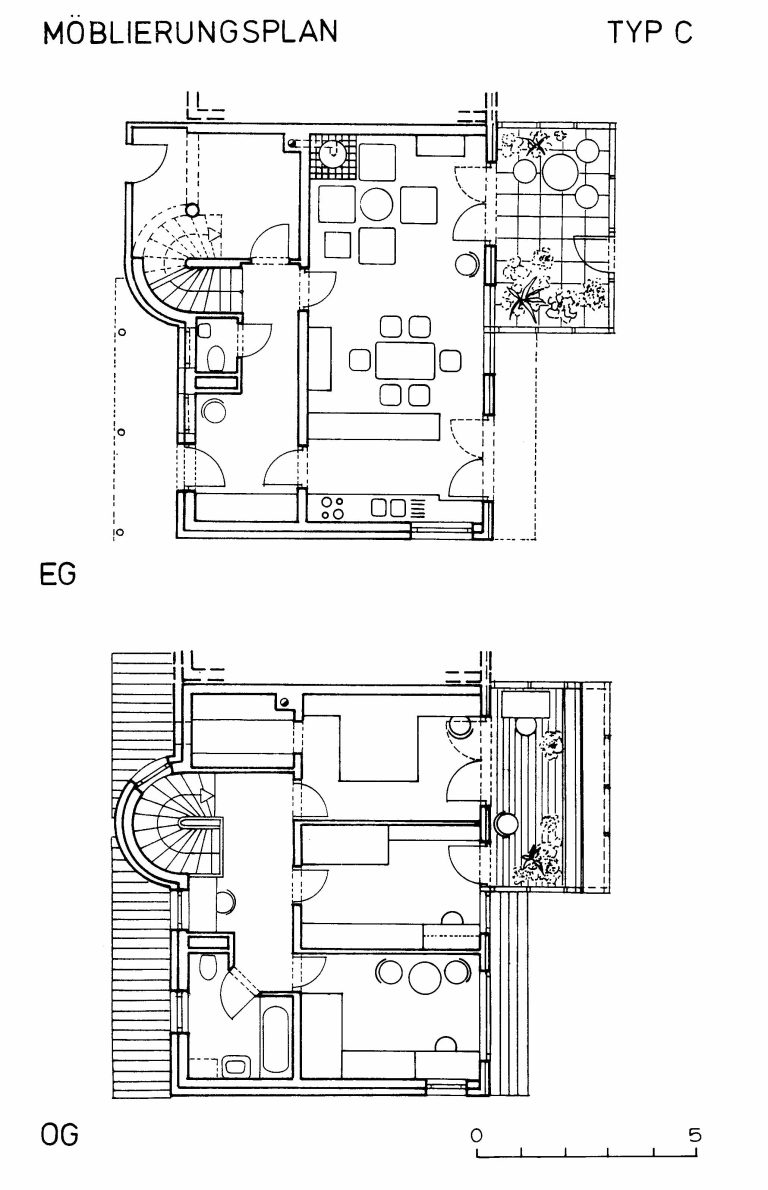

The topic of timber plus passive solar use could not be adopted directly: although these two topics were both “topical”, they cannot be combined directly, because passive solar use requires storage mass (i.e. weight) and this is not provided by pure timber construction (as a lightweight construction). A combination of timber construction and solid construction was therefore chosen and each material was used according to its particular quality. A quasi U-shaped shell (partition walls to the neighbors, as well as the north and middle walls) are solid, as are the base level and the intermediate ceiling in the northern sanitary area. In contrast, the south walls, the roof and the thickness between the ground floor and upper floor are made entirely of wood.

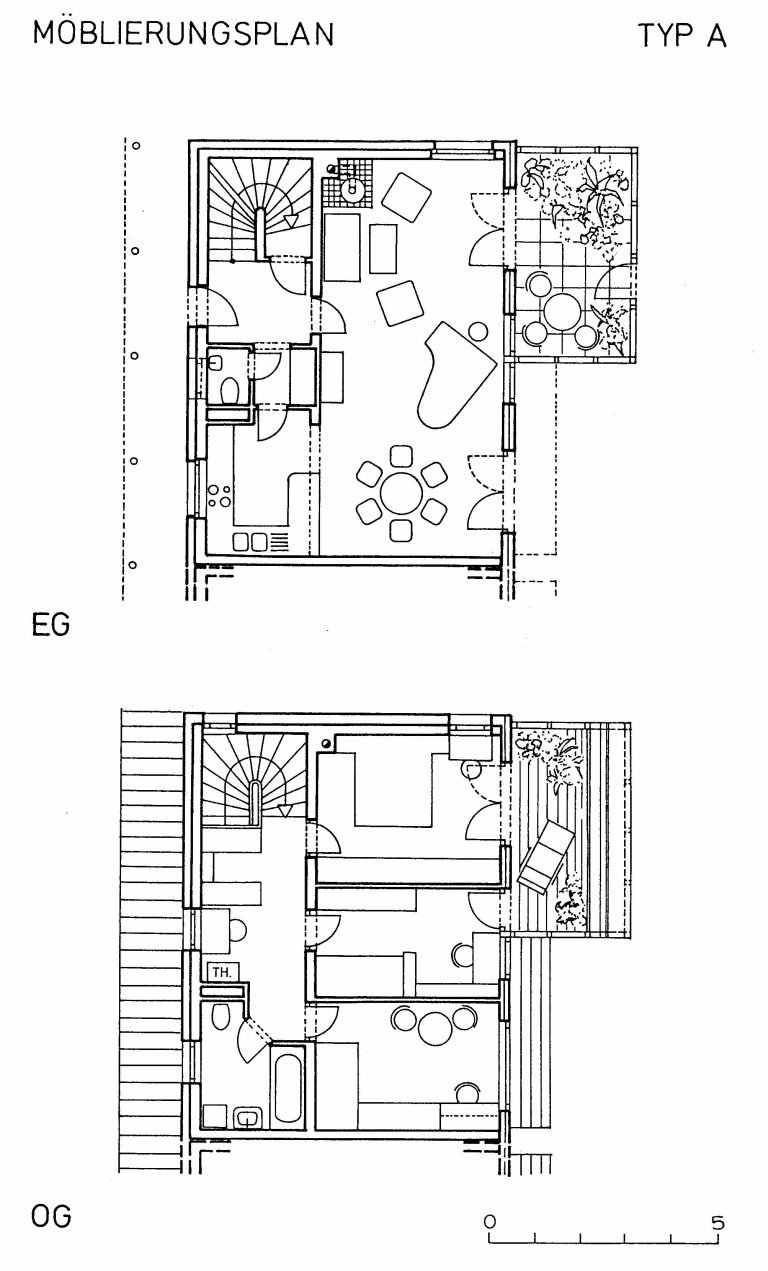

This concept is reflected and overlaid in a very strict zoning in 4 areas with different requirements in terms of construction and use:

- A northern zone with a depth of 2.25 includes all ancillary rooms, utilities and access. Apart from the roof, all structural components here are solid. This northern zone is minimized in volume and kept as low as possible and has only small openings, which not only minimizes the construction costs in this part, but also avoids casting shadows on the next house (low eaves).

- A central zone as a living area (depth 4 m) contains all common rooms, all of which are oriented to the south. This middle zone can also be kept as clean as possible in terms of building biology (from top to bottom: Grass roofing, cork thermal insulation, timber roof construction, bedrooms, timber flooring and solid base plate. Within this zone, there is complete flexibility within each residential unit to move the non-load-bearing walls between the rooms.

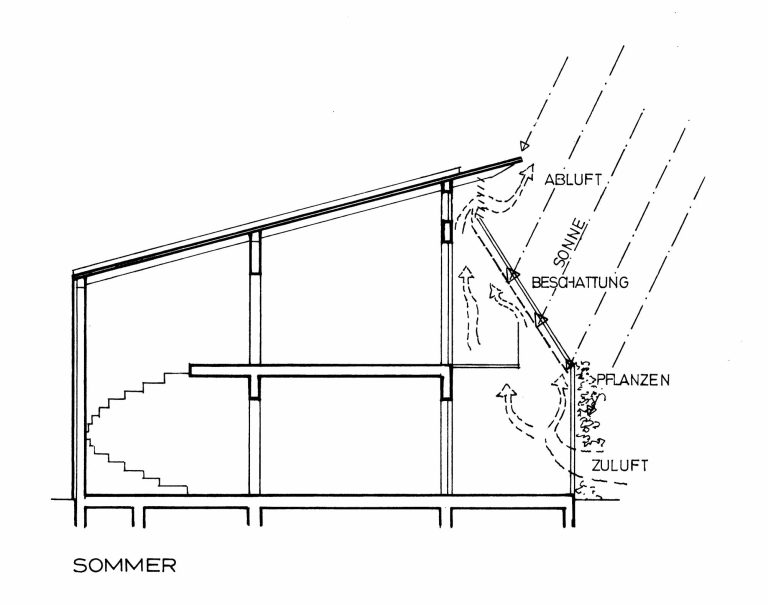

- A southern zone, as a transition area to the garden. This zone contains the solar collector conservatory and the shading equipment (canopy, blinds). This conservatory is attached to the house – independently of the building itself – and, together with the possibility of extending it with balconies, pergolas, marquees and the like, is highly individualized (which is also expressed in the different colors used here).

- A garden area is located in front of each house and at the same time represents the transition to the communal area. In practice, this transition is only defined by the residents themselves.

In principle, a house type was chosen in the planning that initially offered openness for different construction materials and, with a high degree of “standardization”, on the one hand enables industrial construction, but on the other hand offers maximum flexibility and the cheapest installation options (only one “shaft”).

A hollow concrete block (without steel reinforcement and already dried out) was selected as the construction material for the outer walls in the north, east and west – as is usually only used in cellar construction. The walls are insulated with mineral fiber (which is protected with simple, rear-ventilated wooden cladding).

The central wall was made of reinforced concrete – as was the ceiling in the northern “supply zone”. This design is based not least on a simulation calculation, which proved that this “mass” is necessary for solar energy storage as well as protection against overheating in summer. All timber constructions are made of spruce wood. All exterior windows have highly insulating glass (k=1.3 W/m2k). The conservatories are wooden constructions with insulating glazing.

In principle, the solid building materials serve as storage and the wood acts as a “climate regulator” within the apartment.

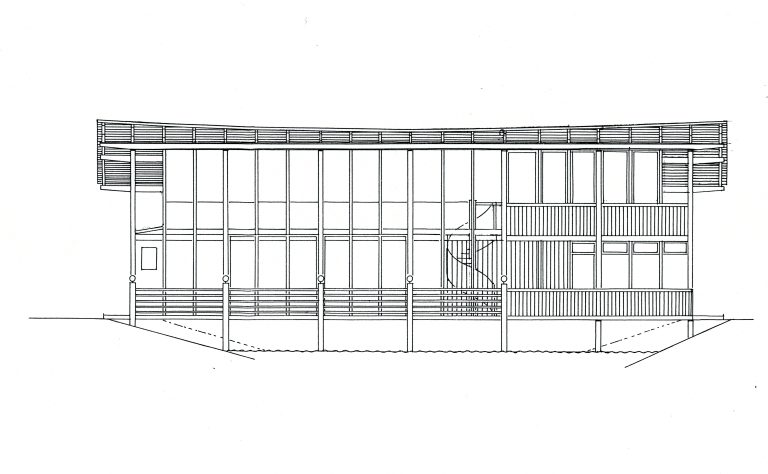

The community house

Of course, it was a certain risk for the planners to provide this spacious community building: not only because the entire costs for this building had to be included in the limited housing costs, but also because the users were unknown until the official approvals were granted and therefore the acceptance of such a building was unknown.

A key factor for the good functioning of the building is probably the generous “opening” of this building “for all residents”.The fairly complete glazing of the façade, which is more or less oriented towards “all” the apartments, makes the building fully and constantly “visible”.This building contains a common room with a gallery (used for parties, child supervision, celebrations, etc.) with a kitchenette and sanitary facilities as well as a sauna with a “relaxation room” (which is used quite actively for gymnastics and fitness exercises).

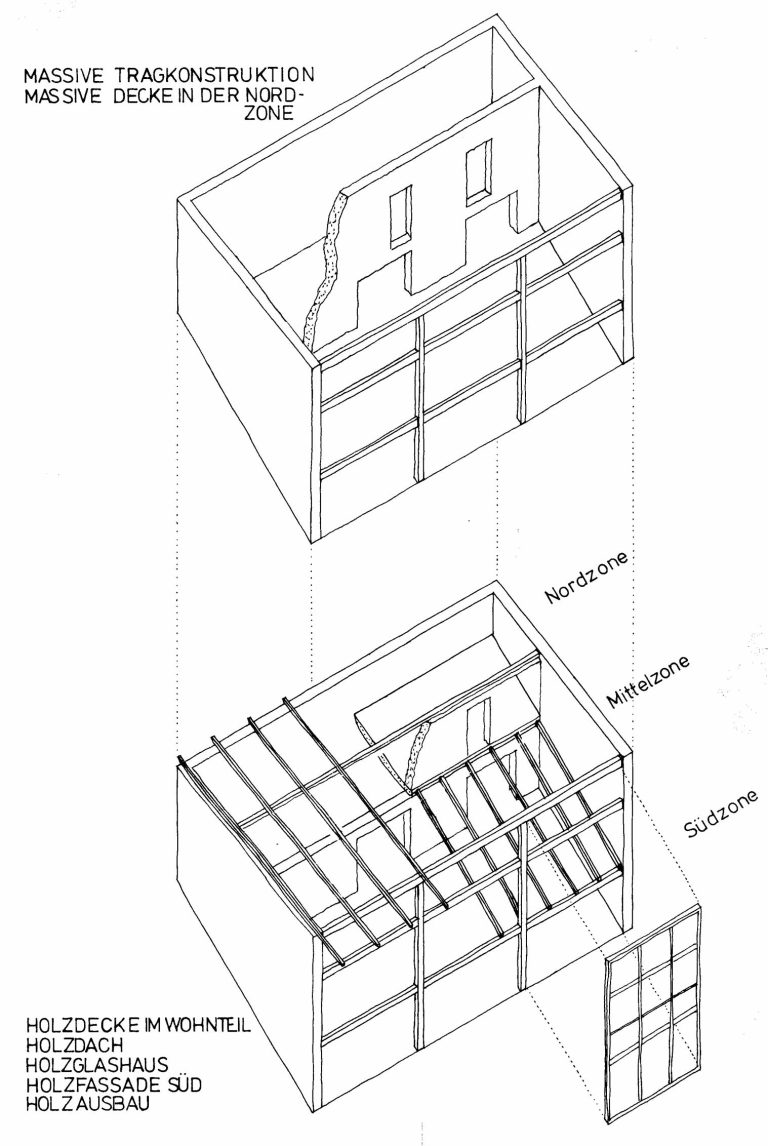

The solar concept

In view of the fact that most energy in the household is used for heating, this is where the most effective measures can be taken to reduce the environmental impact.

With this in mind, the entire system is oriented towards the sun.Not only to bring all the sunlight into the house during the heating season and use it thermally, but also to use this light for special living qualities. So that finally this aspect – namely the consideration of the current environmental situation and the new attitude towards the environment – also presents itself as an “orientation” within the entire building and for the entire structure of the settlement to the outside.

The entire geometry and proportions of the buildings as well as their orientation and arrangement are designed in such a way that mutual shading is avoided and each individual building can “harvest” an optimum of solar radiation in the winter months.In principle, this solar harvest is based on direct solar utilization (via the south-facing windows directly into the rooms where the heat is needed) and isolated passive solar utilization (the heat is obtained in the conservatory and transferred from there to the living rooms via an automatically controlled temperature-dependent valve).The main prerequisites for the use of this solar heat are the high level of thermal insulation and the (storage) mass described above.

It was particularly interesting for the planners that they were planning these facilities for the first time for residents who were initially still anonymous (in previous projects, the use of the sun was the wish of the commissioned users from the outset).However, it turns out that the residents – who were selected from very, very long waiting lists (without any eco-wishes) – use these conservatories extremely intensively and are very good at using them (not a single one of the conservatories has so far degenerated into a “storage room”).So while it was previously suspected that “this way of living” was only really ideal for a small part of the population, the example described in Vienna-Stadlau shows that living with the sun is also of great value to “everyone”.

This “identification with the use of the sun” even goes so far that the residents – in the course of a new building on the neighboring property – argue very strongly with a “right to the sun” (going beyond the currently valid building law).

Summary

All in all, this step in ecological housing construction from “residents’ groups” to the framework of “normal publicly subsidized housing” was of course a very important one for the planners: the argument that these concepts were only suitable for a very special group of residents and a small minority was thus dropped, as was the argument that this construction method was more expensive.

As a result, this project has also become one of the most frequently shown and publicized projects on the part of the municipality of Vienna – which of course contrasts with the modesty of this volume in relation to the total volume of construction in Vienna and Austria.